|

|

| Home | Lermontov | Other Pushkin | Onegin Book I | Book II | Book III | Book IV | Book V | BookVI | BookVII | BookVIII | Gypsies | Chekhov |

CHEKHOV Rothschild's violin

СКРИПКА РОТШИЛЬДА

|

ROTHSCHILD'S

VIOLIN

|

|

| Городок

был маленький, хуже деревни, и жили в нем почти одни только старики,

которые умирали так редко, что даже досадно. В больницу же и в тюремный

замок гробов требовалось очень мало. Одним словом, дела были скверные.

Если бы Яков Иванов был гробовщиком в губернском городе, то, наверное,

он имел бы собственный дом и звали бы его Яковом Матвеичем; здесь же в

городишке звали его просто Яковом, уличное прозвище у него было

почему-то — Бронза, а жил он бедно, как простой мужик, в небольшой

старой избе, где была одна только комната, и в этой комнате помещались

он, Марфа, печь, двухспальная кровать, гробы, верстак и всё хозяйство.

Яков делал гробы хорошие, прочные. Для мужиков и мещан он делал их на свой рост и ни разу не ошибся, так как выше и крепче его не было людей нигде, даже в тюремном замке, хотя ему было уже семьдесят лет. Для благородных же и для женщин делал по мерке и употреблял для этого железный аршин. Заказы на детские гробики принимал он очень неохотно и делал их прямо без мерки, с презрением, и всякий раз, получая деньги за работу, говорил: — Признаться, не люблю заниматься чепухой. Кроме мастерства, небольшой доход приносила ему также игра на скрипке. В городке на свадьбах играл обыкновенно жидовский оркестр, которым управлял лудильщик Моисей Ильич Шахкес, бравший себе больше половины дохода. Так как Яков очень хорошо играл на скрипке, особенно русские песни, то Шахкес иногда приглашал его в оркестр с платою по пятьдесят копеек в день, не считая подарков от гостей. Когда Бронза сидел в оркестре, то у него прежде всего потело и багровело лицо; было жарко, пахло чесноком до духоты, скрипка взвизгивала, у правого уха хрипел контрабас, у левого — плакала флейта, на которой играл рыжий тощий жид с целою сетью красных и синих жилок на лице, носивший фамилию известного богача Ротшильда. И этот проклятый жид даже самое веселое умудрялся играть жалобно. Без всякой видимой причины Яков мало-помалу проникался ненавистью и презрением к жидам, а особенно к Ротшильду; он начинал придираться, бранить его нехорошими словами и раз даже хотел побить его, и Ротшильд обиделся и проговорил, глядя на него свирепо: — Если бы я не уважал вас за талант, то вы бы давно полетели у меня в окошке. Потом заплакал. Поэтому Бронзу приглашали в оркестр не часто, только в случае крайней необходимости, когда недоставало кого-нибудь из евреев. Яков никогда не бывал в хорошем расположении духа, так как ему постоянно приходилось терпеть страшные убытки. Например, в воскресенья и праздники грешно было работать, понедельник — тяжелый день, и таким образом в году набиралось около двухсот дней, когда поневоле приходилось сидеть сложа руки. А ведь это какой убыток! Если кто-нибудь в городе играл свадьбу без музыки или Шахкес не приглашал Якова, то это тоже был убыток. Полицейский надзиратель был два года болен и чахнул, и Яков с нетерпением ждал, когда он умрет, но надзиратель уехал в губернский город лечиться и взял да там и умер. Вот вам и убыток, по меньшей мере рублей на десять, так как гроб пришлось бы делать дорогой, с глазетом. Мысли об убытках донимали Якова особенно по ночам; он клал рядом с собой на постели скрипку и, когда всякая чепуха лезла в голову, трогал струны, скрипка в темноте издавала звук, и ему становилось легче. Шестого мая прошлого года Марфа вдруг занемогла. Старуха тяжело дышала, пила много воды и пошатывалась, но все-таки утром сама истопила печь и даже ходила по воду. К вечеру же слегла. Яков весь день играл на скрипке; когда же совсем стемнело, взял книжку, в которую каждый день записывал свои убытки, и от скуки стал подводить годовой итог. Получилось больше тысячи рублей. Это так потрясло его, что он хватил счетами о пол и затопал ногами. Потом поднял счеты и опять долго щелкал и глубоко, напряженно вздыхал. Лицо у него было багрово и мокро от пота. Он думал о том, что если бы эту пропащую тысячу рублей положить в банк, то в год проценту накопилось бы самое малое — сорок рублей. Значит, и эти сорок рублей тоже убыток. Одним словом, куда ни повернись, везде только убытки и больше ничего. — Яков! — позвала Марфа неожиданно. — Я умираю! Он оглянулся на жену. Лицо у нее было розовое от жара, необыкновенно ясное и радостное. Бронза, привыкший всегда видеть ее лицо бледным, робким и несчастным, теперь смутился. Похоже было на то, как будто она в самом деле умирала и была рада, что наконец уходит навеки из этой избы, от гробов, от Якова... И она глядела в потолок и шевелила губами, и выражение у нее было счастливое, точно она видела смерть, свою избавительницу, и шепталась с ней. Был уже рассвет, в окно видно было, как горела утренняя заря. Глядя на старуху, Яков почему-то вспомнил, что за всю жизнь он, кажется, ни разу не приласкал ее, не пожалел, ни разу не догадался купить ей платочек или принести со свадьбы чего-нибудь сладенького, а только кричал на нее, бранил за убытки, бросался на нее с кулаками; правда, он никогда не бил ее, но все-таки пугал, и она всякий раз цепенела от страха. Да, он не велел ей пить чай, потому что и без того расходы большие, и она пила только горячую воду. И он понял, отчего у нее теперь такое странное, радостное лицо, и ему стало жутко. Дождавшись утра, он взял у соседа лошадь и повез Марфу в больницу. Тут больных было немного и потому пришлось ему ждать недолго, часа три. К его великому удовольствию, в этот раз принимал больных не доктор, который сам был болен, а фельдшер Максим Николаич, старик, про которого все в городе говорили, что хотя он и пьющий и дерется, но понимает больше, чем доктор. — Здравия желаем, — сказал Яков, вводя старуху в приемную. — Извините, всё беспокоим вас, Максим Николаич, своими пустяшными делами. Вот, изволите видеть, захворал мой предмет. Подруга жизни, как это говорится, извините за выражение... Нахмурив седые брови и поглаживая бакены, фельдшер стал оглядывать старуху, а она сидела на табурете сгорбившись и, тощая, остроносая, с открытым ртом, походила в профиль на птицу, которой хочется пить. — М-да... Так... — медленно проговорил фельдшер и вздохнул. — Инфлуэнца, а может и горячка. Теперь по городу тиф ходит. Что ж? Старушка пожила, слава богу... Сколько ей? — Да без года семьдесят, Максим Николаич. — Что ж? Пожила старушка. Пора и честь знать. — Оно, конечно, справедливо изволили заметить, Максим Николаич, — сказал Яков, улыбаясь из вежливости, — и чувствительно вас благодарим за вашу приятность, но позвольте вам выразиться, всякому насекомому жить хочется. — Мало ли чего! — сказал фельдшер таким тоном, как будто от него зависело жить старухе или умереть. — Ну, так вот, любезный, будешь прикладывать ей на голову холодный компресс и давай вот эти порошки по два в день. А за сим досвиданция, бонжур. По выражению его лица Яков видел, что дело плохо и что уж никакими порошками не поможешь; для него теперь ясно было, что Марфа помрет очень скоро, не сегодня-завтра. Он слегка толкнул фельдшера под локоть, подмигнул глазом и сказал вполголоса: — Ей бы, Максим Николаич, банки поставить. — Некогда, некогда, любезный. Бери свою старуху и уходи с богом. Досвиданция. — Сделайте такую милость, — взмолился Яков. — Сами изволите знать, если б у нее, скажем, живот болел или какая внутренность, ну, тогда порошки и капли, а то ведь в ней простуда! При простуде первое дело — кровь гнать, Максим Николаич. А фельдшер уже вызвал следующего больного, и в приемную входила баба с мальчиком. — Ступай, ступай... — сказал он Якову, хмурясь. — Нечего тень наводить. — В таком случае поставьте ей хоть пьявки! Заставьте вечно бога молить! Фельдшер вспылил и крикнул: — Поговори мне еще! Ддубина... Яков тоже вспылил и побагровел весь, но не сказал ни слова, а взял под руку Марфу и повел ее из приемной. Только когда уж садились в телегу, он сурово и насмешливо поглядел на больницу и сказал: — Насажали вас тут артистов! Богатому небось поставил бы банки, а для бедного человека и одной пьявки пожалел. Ироды! Когда приехали домой, Марфа, войдя в избу, минут десять простояла, держась за печку. Ей казалось, что если она ляжет, то Яков будет говорить об убытках и бранить ее за то, что она всё лежит и не хочет работать. А Яков глядел на нее со скукой и вспоминал, что завтра Иоанна богослова, послезавтра Николая чудотворца, а потом воскресенье, потом понедельник — тяжелый день. Четыре дня нельзя будет работать, а наверное Марфа умрет в какой-нибудь из этих дней; значит, гроб надо делать сегодня. Он взял свой железный аршин, подошел к старухе и снял с нее мерку. Потом она легла, а он перекрестился и стал делать гроб. Когда работа была кончена, Бронза надел очки и записал в свою книжку: «Марфе Ивановой гроб — 2 р. 40 к.». И вздохнул. Старуха всё время лежала молча с закрытыми глазами. Но вечером, когда стемнело, она вдруг позвала старика. — Помнишь, Яков? — спросила она, глядя на него радостно. — Помнишь, пятьдесят лет назад нам бог дал ребеночка с белокурыми волосиками? Мы с тобой тогда всё на речке сидели и песни пели... под вербой. — И, горько усмехнувшись, она добавила: — Умерла девочка. Яков напряг память, но никак не мог вспомнить ни ребеночка, ни вербы. — Это тебе мерещится, — сказал он. Приходил батюшка, приобщал и соборовал. Потом Марфа стала бормотать что-то непонятное и к утру скончалась. Старухи-соседки обмыли, одели и в гроб положили. Чтобы не платить лишнего дьячку, Яков сам читал псалтырь, и за могилку с него ничего не взяли, так как кладбищенский сторож был ему кум. Четыре мужика несли до кладбища гроб, но не за деньги, а из уважения. Шли за гробом старухи, нищие, двое юродивых, встречный народ набожно крестился... И Яков был очень доволен, что всё так честно, благопристойно и дешево и ни для кого не обидно. Прощаясь в последний раз с Марфой, он потрогал рукой гроб и подумал: «Хорошая работа!» Но когда он возвращался с кладбища, его взяла сильная тоска. Ему что-то нездоровилось: дыхание было горячее и тяжкое, ослабели ноги, тянуло к питью. А тут еще полезли в голову всякие мысли. Вспомнилось опять, что за всю свою жизнь он ни разу не пожалел Марфы, не приласкал. Пятьдесят два года, пока они жили в одной избе, тянулись долго-долго, но как-то так вышло, что за всё это время он ни разу не подумал о ней, не обратил внимания, как будто она была кошка или собака. А ведь она каждый день топила печь, варила и пекла, ходила по воду, рубила дрова, спала с ним на одной кровати, а когда он возвращался пьяный со свадеб, она всякий раз с благоговением вешала его скрипку на стену и укладывала его спать, и всё это молча, с робким, заботливым выражением. Навстречу Якову, улыбаясь и кланяясь, шел Ротшильд. — А я вас ищу, дяденька! — сказал он. — Кланялись вам Мойсей Ильич и велели вам зараз приходить к ним. Якову было не до того. Ему хотелось плакать. — Отстань! — сказал он и пошел дальше. — А как же это можно? — встревожился Ротшильд, забегая вперед. — Мойсей Ильич будут обижаться! Они велели зараз! Якову показалось противно, что жид запыхался, моргает и что у него так много рыжих веснушек. И было гадко глядеть на его зеленый сюртук с темными латками и на всю его хрупкую, деликатную фигуру. — Что ты лезешь ко мне, чеснок? — крикнул Яков. — Не приставай! Жид рассердился и тоже крикнул: — Но ви пожалуста потише, а то ви у меня через забор полетите! — Прочь с глаз долой! — заревел Яков и бросился на него с кулаками. — Житья нет от пархатых! Ротшильд помертвел от страха, присел и замахал руками над головой, как бы защищаясь от ударов, потом вскочил и побежал прочь что есть духу. На бегу он подпрыгивал, всплескивал руками, и видно было, как вздрагивала его длинная, тощая спина. Мальчишки обрадовались случаю и бросились за ним с криками: «Жид! Жид!» Собаки тоже погнались за ним с лаем. Кто-то захохотал, потом свистнул, собаки залаяли громче и дружнее... Затем, должно быть, собака укусила Ротшильда, так как послышался отчаянный, болезненный крик. Яков погулял по выгону, потом пошел по краю города, куда глаза глядят, и мальчишки кричали: «Бронза идет! Бронза идет!» А вот и река. Тут с писком носились кулики, крякали утки. Солнце сильно припекало, и от воды шло такое сверканье, что было больно смотреть. Яков прошелся по тропинке вдоль берега и видел, как из купальни вышла полная краснощекая дама, и подумал про неё: «Ишь ты, выдра!» Недалеко от купальни мальчишки ловили на мясо раков; увидев его, они стали кричать со злобой: «Бронза! Бронза!» А вот широкая старая верба с громадным дуплом, а на ней вороньи гнезда... И вдруг в памяти Якова, как живой, вырос младенчик с белокурыми волосами и верба, про которую говорила Марфа. Да, это и есть та самая верба — зеленая, тихая, грустная... Как она постарела, бедная! Он сел под нее и стал вспоминать. На том берегу, где теперь заливной луг, в ту пору стоял крупный березовый лес, а вон на той лысой горе, что виднеется на горизонте, тогда синел старый-старый сосновый бор. По реке ходили барки. А теперь всё ровно и гладко, и на том берегу стоит одна только березка, молоденькая и стройная, как барышня, а на реке только утки да гуси, и не похоже, чтобы здесь когда-нибудь ходили барки. Кажется, против прежнего и гусей стало меньше. Яков закрыл глаза, и в воображении его одно навстречу другому понеслись громадные стада белых гусей. Он недоумевал, как это вышло так, что за последние сорок или пятьдесят лет своей жизни он ни разу не был на реке, а если, может, и был, то не обратил на нее внимания? Ведь река порядочная, не пустячная; на ней можно было бы завести рыбные ловли, а рыбу продавать купцам, чиновникам и буфетчику на станции и потом класть деньги в банк; можно было бы плавать в лодке от усадьбы к усадьбе и играть на скрипке, и народ всякого звания платил бы деньги; можно было бы попробовать опять гонять барки — это лучше, чем гробы делать; наконец, можно было бы разводить гусей, бить их и зимой отправлять в Москву; небось одного пуху в год набралось бы рублей на десять. Но он прозевал, ничего этого не сделал. Какие убытки! Ах, какие убытки! А если бы всё вместе — и рыбу ловить, и на скрипке играть, и барки гонять, и гусей бить, то какой получился бы капитал! Но ничего этого не было даже во сне, жизнь прошла без пользы, без всякого удовольствия, пропала зря, ни за понюшку табаку; впереди уже ничего не осталось, а посмотришь назад — там ничего, кроме убытков, и таких страшных, что даже озноб берет. И почему человек не может жить так, чтобы не было этих потерь и убытков? Спрашивается, зачем срубили березняк и сосновый бор? Зачем даром гуляет выгон? Зачем люди делают всегда именно не то, что нужно? Зачем Яков всю свою жизнь бранился, рычал, бросался с кулаками, обижал свою жену и, спрашивается, для какой надобности давеча напугал и оскорбил жида? Зачем вообще люди мешают жить друг другу? Ведь от этого какие убытки! Какие страшные убытки! Если бы не было ненависти и злобы, люди имели бы друг от друга громадную пользу. Вечером и ночью мерещились ему младенчик, верба, рыба, битые гуси, и Марфа, похожая в профиль на птицу, которой хочется пить, и бледное, жалкое лицо Ротшильда, и какие-то морды надвигались со всех сторон и бормотали про убытки. Он ворочался с боку на бок и раз пять вставал с постели, чтобы поиграть на скрипке. Утром через силу поднялся и пошел в больницу. Тот же Максим Николаич приказал ему прикладывать к голове холодный компресс, дал порошки, и по выражению его лица и по тону Яков понял, что дело плохо и что уж никакими порошками не поможешь. Идя потом домой, он соображал, что от смерти будет одна только польза: не надо ни есть, ни пить, ни платить податей, ни обижать людей, а так как человек лежит в могилке не один год, а сотни, тысячи лет, то, если сосчитать, польза окажется громадная. От жизни человеку — убыток, а от смерти — польза. Это соображение, конечно, справедливо, но все-таки обидно и горько: зачем на свете такой странный порядок, что жизнь, которая дается человеку только один раз, проходит без пользы? Не жалко было умирать, но как только дома он увидел скрипку, у него сжалось сердце и стало жалко. Скрипку нельзя взять с собой в могилу, и теперь она останется сиротой и с нею случится то же, что с березняком и с сосновым бором. Всё на этом свете пропадало и будет пропадать! Яков вышел из избы и сел у порога, прижимая к груди скрипку. Думая о пропащей, убыточной жизни, он заиграл, сам не зная что, но вышло жалобно и трогательно, и слезы потекли у него по щекам. И чем крепче он думал, тем печальнее пела скрипка. Скрипнула щеколда раз-другой, и в калитке показался Ротшильд. Половину двора прошел он смело, но, увидев Якова, вдруг остановился, весь съежился и, должно быть, от страха стал делать руками такие знаки, как будто хотел показать на пальцах, который теперь час. — Подойди, ничего, — сказал ласково Яков и поманил его к себе. — Подойди! Глядя недоверчиво и со страхом, Ротшильд стал подходить и остановился от него на сажень. — А вы, сделайте милость, не бейте меня! — сказал он, приседая. — Меня Мойсей Ильич опять послали. Не бойся, говорят, поди опять до Якова и скажи, говорят, что без их никак невозможно. В среду швадьба... Да-а! Господин Шаповалов выдают дочку жа хорошего целовека... И швадьба будет богатая, у-у! — добавил жид и прищурил один глаз. — Не могу... — проговорил Яков, тяжело дыша. — Захворал, брат. И опять заиграл, и слезы брызнули из глаз на скрипку. Ротшильд внимательно слушал, ставши к нему боком и скрестив на груди руки. Испуганное, недоумевающее выражение на его лице мало-помалу сменилось скорбным и страдальческим, он закатил глаза, как бы испытывая мучительный восторг, и проговорил: «Ваххх!..» И слезы медленно потекли у него по щекам и закапали на зеленый сюртук. И потом весь день Яков лежал и тосковал. Когда вечером батюшка, исповедуя, спросил его, не помнит ли он за собою какого-нибудь особенного греха, то он, напрягая слабеющую память, вспомнил опять несчастное лицо Марфы и отчаянный крик жида, которого укусила собака, и сказал едва слышно: — Скрипку отдайте Ротшильду. — Хорошо, — ответил батюшка. И теперь в городе все спрашивают: откуда у Ротшильда такая хорошая скрипка? Купил он ее или украл, или, быть может, она попала к нему в заклад? Он давно уже оставил флейту и играет теперь только на скрипке. Из-под смычка у него льются такие же жалобные звуки, как в прежнее время из флейты, но когда он старается повторить то, что играл Яков, сидя на пороге, то у него выходит нечто такое унылое и скорбное, что слушатели плачут, и сам он под конец закатывает глаза и говорит: «Ваххх!..» И эта новая песня так понравилась в городе, что Ротшильда приглашают к себе наперерыв купцы и чиновники и заставляют играть ее по десяти раз.

СКРИПКА РОТШИЛЬДА Впервые — «Русские ведомости», 1894, № 37, 6 февраля, стр. 2. Подпись: Антон Чехов.

|

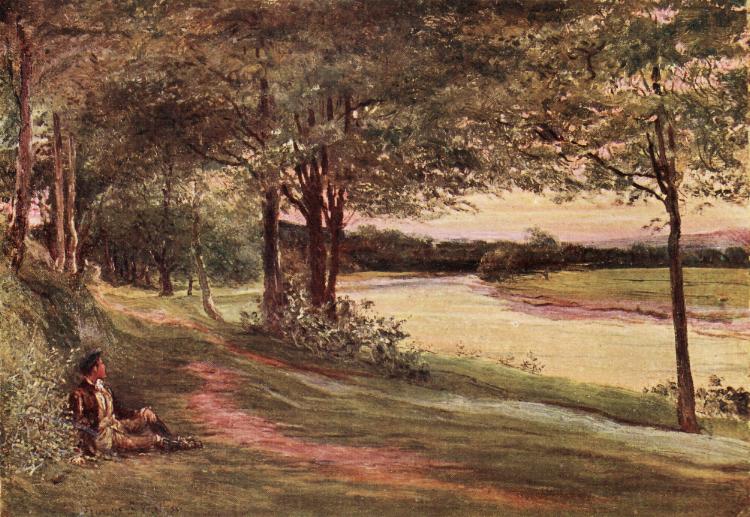

It was a

wretched, small town, worse than a village, and mostly full

of old people, who died so infrequently that it was very annoying. From

the hospital and the lock-up very few coffins were ordered. In a word,

business was dire. If Yakov Ivanov had been an undertaker in a

provincial town, then probably he would have had his own house and

people would have called him Yakov Matveich, whereas here in this

wretched place he was plain Yakov and his nickname on the streets for

some reason was Bronze. He lived in an impoverished state, like a

peasant, in a small hut which had only one room, and in this room were

housed himself, Martha, a stove, a double bed, coffins, a workbench,

and all the tools of his trade. Yakov made good, sturdy coffins. For peasants and artisans he made them based on his own size, and never got it wrong, since there were no people taller or more hefty than he was, even in the lock-up, and even though he was seventy. For the upper classes and for women he made the coffins to measure, and for this he used his steel rule. He was very unwilling to take orders for children's coffins and he would make them without taking measurements, and with contempt. In such cases, when he took the money for the work, he would always say "To tell you the truth, I don't like messing with trivialities." Apart from his trade, he got a small income from playing the violin. In their little town, at weddings, a Jewish orchestra would usually play. It was conducted by the tinsmith, Moysey Ilyich Shakkhes, who took for himself more than half the fees. Since Yakov was such a good violin player, especially of Russian songs, Moysey occasionally invited him to join the band for a payment of half a rouble for the day, plus any gifts which the guests might give him. Whenever Bronze sat in the orchestra, he would first of all start to perspire and his face reddened. It was hot, there was a stifling smell of garlic, the violin squealed, in his right ear the double bass wheezed, in his left the flute moaned plaintively. This was played by a red haired emaciated Jew with a whole network of red and blue veins on his face. He bore the surname of that well known wealthy Jew Rothschild. And this damned Jew contrived to make even the most merry tune sound mournful. For no apparent reason, Yakov gradually became infected with a hatred and contempt of Jews, but especially for this Rothschild; he started to pick on him and abuse him with harsh words and once he even wanted to beat him. Rothschild took offence and told him, looking at him fiercely, "If I didn't respect you for your talent, then you would long ago have gone flying out of the window." Then he burst into tears. For this reason Bronze was not often asked to join the orchestra, except in cases of extreme necessity, when one of the Jews was not able to attend. Yakov was never in a good mood, because he was always having to put up with dreadful losses. For example on Sundays and other holy days it was a sin to work, and Mondays were also proscribed days, so that in total there were around two hundred days in the year when, like it or not, you had to sit at home doing nothing. But what a loss of income this was! If somebody in the town had a wedding without music, or if Shakkhes did not invite him to join the orchestra, that was also a loss. The police superintendent had been ill for two years and was consumptive, and Yakov waited patiently for him to die, but the superintendent went off to the provincial capital for treatment and went and died there. There was a complete loss for you, at least ten roubles, since he would have wanted an expensive coffin, with silk brocade. Thoughts of his losses troubled him particularly at night. He would put the violin on the bed beside him, and then when all that nonsense crept into his head he touched its strings, the violin would make a sound in the darkness and Yakov felt better. On the sixth of May of the previous year Martha suddenly became ill. The old woman had difficult breathing, she drank a lot of water and swayed around, but all the same, in the morning she stoked up the stove and even went to fetch water. Towards evening she lay down ill. Yakov played all day on his violin. When it became completely dark, he took the book in which he recorded each day all his losses, and out of boredom began to tot up the year's total. It came to more than a thousand roubles. This shook him so much that he flung the abacus on to the floor and trampled on it. Then he picked it up, rattled away with the beads for a long time and gave a deep, heartfelt sigh. His face was red and wet with perspiration. He thought about the fact that if he had deposited the lost thousand roubles in the bank, then over a year it would have accumulated at the very least another forty roubles. Evidently then, that forty roubles was yet another loss. In short, whatever way you turned, it was one loss after another and nothing else. "Yakov!" Martha called to him unexpectedly. "I'm dying." He looked round at his wife. Her face was rosy with fever, but unusually clear and radiant. Bronze, who was habituated to seeing his wife's face always pale, timid and unhappy, felt confused. It was if she was indeed dying and was glad that at last she would be leaving this hut for ever, leaving the coffins and Yakov. She looked at the ceiling and her lips were fluttering, her expression was blissful, as if she saw death, her saviour, and was whispering to it. It was already dawn, the morning glow was by now visible, lighting up the window. Looking on the old woman Yakov for some reason remembered that he had never been tender with her, never pitied her, not once had he ever thought to buy her a scarf or bring her some sweets from one of the weddings, but he had only shouted at her, abused her because of his losses, rushed at her brandishing his fists. It's true, he had never beaten her, but all the same he terrified her, and each time when he rushed at her she was struck rigid with fear. Yes, he forbade her to drink tea, because apart from that living expenses were so high, and she only drank hot water. He understood why now she had such a strange happy expression on her face, and it made him feel uneasy. Having waited until the morning, he borrowed a horse from a neighbour and took Martha to the hospital. At the hospital it turned out that there were not many patients and he only had to wait three hours. To his great delight it was not the doctor receiving patients this morning, who was himself ill, but the assistant, Maksim Nikolaich, an old boy, about whom in the town the gossip was that, although he liked the bottle and was a quarreler, he knew more about medicine than the doctor. "Good day to you Sir" said Yakov, bringing his old lady into the reception room. "Pardon me Maksim Nikolaich, for always pestering you with my trifling problems. But as you will be kind enough to see, my good woman has taken ill. A friend for life, as they say, if you'll pardon the expression." Knitting his grey eyebrows and stroking his

side whiskers, the assistant started to examine the old woman as she

sat on a stool, bent over, and with her emaciated look, her sharp nose

and her mouth open she looked in profile like a bird that needed to

drink. "A year short of seventy, Maksim Nikolaich" "Well then, she's had a life. It's time to know one's place.1" "That's true, it's a fair comment, Maksim Nikolaich," said Yakov smiling out of politeness, "and we thank you from our hearts for your kindness, but if I may express it so, every insect wants to live." "As if I didn't know!" said the assistant in such a tone as if the life or death of the old woman depended on him. "Well then, dear fellow, you must put a cold compress on her head, and give her these powders twice a day. So that's all, till we meet again. Bonjour." By the expression on his face Yakov saw that things were in a bad way and that no powders of any sort would be of any use; it was clear to him now that Martha would be dying very soon, either today or tomorrow. He touched the assistant lightly below the elbow, winked an eye and said in a low voice "You could of course, Maksim Nikolaich, try the cups2 on her." "There's no time, no time, my dear fellow. Take your old woman and be on your way, in God's name. Adieu" "If you would only be so gracious," Yakov resorted to entreaty, "you yourself are so good as to know, if it were, shall we say, a stomach illness, or something internal, then of course powders or drops, but look, she has after all taken a chill! If it's a chill, then the first thing to do is to let blood3." But the assistant had already called the next patient' and a woman with her boy came into the reception room. "On your way. On your way." he said to Yakov frowning. "You're taking up space here." "In that case you could at least apply the leeches to her. Let me be eternally grateful to you." The assistant flared up and shouted at him. "Are you still talking to me, you blockhead!" Yakov also flared up, but he didn't say a word. He took Martha under the arm and led her out of the reception room. Only when they were sitting in the cart did he look fiercely and sneeringly at the hospital. "You're a bunch of artists in that place, aren't you! For a rich person I'm sure you'd have given them the cups, but for someone who's poor you begrudge a single leech. Monsters!" When they got home Martha, when she went in to the hut, stood upright for ten minutes holding on to the stove. It seemed that if she lay down Yakov would start to talk about losses and scold her because she was lying down and not wanting to work. But Yakov looked at her with a bored look and remembered that tomorrow was the feast of St. John the Divine, the day after it was Nikolay the miracle worker, then it was Sunday, then Monday, which was an ill omened day. For four days it would be impossible to work, and probably Martha would die on one of those days, so that meant the coffin would have to be made today. He took his steel rule, went up to the old woman and measured her. Then she went to lie down, he made the sign of the cross and started to make the coffin. When the work was finished Bronze put on his spectacles and wrote in his account book : For Martha Ivanovna, coffin - 2 roubles 40k. Then he sighed. The old girl was still lying with her eyes shut. But in the evening when it started to darken she suddenly called out to her old man "Do you remember Yakov?" she said, looking at him with a happy expression. "Do you remember, fifty years ago God gave us a little child with lovely fair hair. You and I spent all the time then sitting beside the river and sang songs to her ... beneath the willow." Then she laughed bitterly and added "The little girl died." Yakov strained his memory, but there was no way in which he could remember the little child, or the willow. "You're just dreaming," he said. The priest came and gave her the last rites and holy communion. Then Martha started to mumble something incomprehensible, and towards morning she died. The neigbouring old women washed the body, dressed her and laid her in the coffin. So as not to pay overmuch to the deacon, Yakov himself read the psalter and he did not pay anything for the grave, since the gravedigger was one of his cronies. Four men carried the coffin to the cemetery, not for money, but out of respect. Beggars, some old people and two holy fools in Christ followed the coffin' and those meeting it devoutly crossed themselves. Yakov was very satisfied that all was done so decently and honourably, and so cheaply, and nobody had been offended. Saying farewell for the last time to Martha he touched her forehead with his hand and thought 'That was good work'. But when he returned home from the cemetery an awful grief and sickness took hold of him. His breathing became burning and heavy, his legs felt weak and he was desperately thirsty. And at this point also all sorts of thoughts came into his head. He remembered again that in all his life he had never taken pity on Martha, not once been tender with her. For fifty two years he had shared the same hut with her, the years stretched on and on, but somehow it turned out that in all that time he never once thought about her, paid her no attention, as if she had been a cat or a dog. And yet everyday she stoked up the stove, stewed and baked, went to fetch water, cut the firewood, slept in the same bed with him, and when he returned home drunk from a wedding, each time she would hang his violin on the wall with reverence, and put him to bed, doing it all silently, with a timid, care-worn expression. Rothschild in the distance was coming to see him, smiling and bowing. "I've come to find you uncle!", he said. "Moysey Ilyich sends his respects and asks you to join him as soon as possible." Yakov did not feel like doing this. He only wanted to cry. "Leave me alone!" he said and moved away. "But how can this be?" said Rothschild, running forward in a perturbed way. "Moysey Ilyich will take offence. He said come straight away!" Yakov felt disgust at Rothschild's breathlessness, the way his eyes blinked and the fact that he had so many red freckles. It was sickening to look at his green jacket with dark patches and in general at all his frail, delicate figure. "Why are you coming after me, you stinking garlic? Stop pestering!" he shoutede. The Jew, in his turn, also got angry and shouted. "You just speak a bit more quietly, otherwise you'll find yourself flying over this fence!" "Get out of my sight!" roared Yakov and rushed at him brandishing his fists. "You pestilential creatures just won't let us live!" Rothschild nearly died with terror, he crouched to the ground and waved his hands above his head as if defending himself from the blows, then he leapt up and ran off as fast as his legs would carry him. As he ran he leapt up and threw his hands in the air, and you could see how his long, spindly back shuddered. Little boys were delighted with the opportunity and ran after him shouting "Jew! Jew!" Dogs also chased after him and barked. Somebody laughed, then whistled, and the dogs started barking louder and more in concert ... Then, evidently, a dog bit Rothschild, since you could hear his despairing, agonised cry. Yakov set off across the common, then he made for the edge of the town, wherever his fancy took him, and the boys shouted out, "There goes Bronze. There goes Bronze!" Then he came to the river. Here the curlews were soaring and shrieking, the ducks quacked. The sun was baking hot and there was such a dazzling light coming off the water that it was painful to look at it. Yakov went along the path by the bank and saw how a fat, red cheeked woman was coming out of the bathing house, and he thought about her 'Look at you, you otter!' Not far from the bathing house boys were catching crayfish with bits of meat. When they saw Yakov, they started to shout spitefully "Bronze! Bronze!" But here was a huge wide old willow tree with a great hollow in it and a crow's nest on top. And suddenly there arose in his memory, as if it were alive, the young baby with fair hair, and the willow tree of which Martha had spoken. Yes, this is that very same willow - green, silent, mournful... How it has aged, poor old thing! He sat under it and started to remember. On the other bank, where there was now a water meadow, at that time there was a large birch wood, and there, on that bald hill which could be seen on the horizon, there used to be the blue haze of a really old pine forest. Barges passed along the river. But now all was even and smooth, and on the opposite bank there was only a single birch tree, young and slender, like a young lady, and on the river there were only ducks and geese, and it did not seem feasible that here, in the past, barges passed to and fro. It even seemed that, compared with former times, there were less geese. Yakov closed his eyes and in his imagination huge flocks of white geese came floating by one after another. He was puzzled how it could be that for the last forty or fifty years of his life he had not once been down to the river, or if he had been, he had not paid it the slightest attention. After all it was a substantial river, no petty rivulet. You could set up on it stands for fishing and sell the fish to merchants, to clerks and to the station buffet and then deposit the money in the bank; you could sail in a boat from bank to bank playing the violin and people of all callings would pay good money; you could try once again to get the barge traffic going - that would be better than making coffins; and finally you could raise geese, kill them in the winter and sell them to Moscow; probably the down alone would raise ten roubles in a year. But he had sat around gaping and done none of those things. What a loss! Ah, what a loss! If you take the whole lot together, the fishery, the violin on the boat, the barge traffic, the geese, what a capital you would make out of it. But none of this had happened, not even in his dreams, life had slipped past uselessly, without any pleasure, it had just gone for nothing, not even for a pinch of tobacco. Ahead of him nothing remained, and if he looked back, there was nothing there either, except loss, and such terrible losses that they turn you to ice. And why couldn't a man exist without enduring these losses and this waste. One might ask why the birch wood and the pine forest were cut down? Why was he walking pointlessly over the common? Why was it that people always did things which were better not done? Why was it that Yakov all his life scolded, roared, rushed at his wife with his fists, offended her, and why, one might ask, what need was there for him just now to terrify and insult that Jew? Why is it in general that people prevent each other from living? And what a loss stems from all that! What terrible losses! If there were none of this hatred and evil, people would derive such a huge advantage from each other. In the evening and at night he saw in his mind's eye the baby, the willow, the fish, the goose production, and Martha with her profile that was like a bird that wanted to drink, and the pale, pitiful face of Rothschild, and some sort of ugly snouts moved in on him from all sides and muttered about losses. He tossed from side to side and five times he got out of bed to play the violin. In the morning he forced himself to get up and go to the hospital. The same Maksim Nikolaich told him to put a cold compress on his head and gave him some powders. By the expression on his face and by his tone Yakov understood that he was in a bad way and that no powders could do any good. As he was going home it occurred to him that there would be one gain at least: there would be no need to eat, nor drink, nor pay taxes, nor offend people, and since a man lies in the grave not for a year, but for hundreds, thousands of years, then if you reckon it up, the gain is enormous. From the life of a human there is loss, but from death, gain. This thought, it is true, was just, but nevertheless it was offensive and bitter: why was it that on the earth there was such a strange ordering of things that life, which is given to a person only once, passes without any advantage or gain? He was not sorry about dying, but as soon as he came home and saw his violin it pinched his heart and he felt miserable. He couldn't take the violin with him to the grave, and now it would remain an orphan and suffer the same fate as the birch wood and the pine forest. Everything on this earth went to ruin, and would go to ruin. Yakov went out of the hut and sat in the doorway, pressing the fiddle to his breast. Thinking of this life full of losses and ruin he started to play, not knowing what it was he was playing, but it came out plaintively and deeply moving, and tears trickled down his cheeks. The more deeply he plunged into thought, the more plaintively the violin sang its tune. The latch of the gate clicked a couple of times and Rothschild appeared in the gateway. Half of the yard he crossed confidently, but, seeing Yakov, he suddenly stopped., shrank into himself, and out of terror he started to make signs with his hands as if he were trying to show what time it was."Come on, you needn't worry," said Yakov in a kindly tone. "Come on." And he beckoned Rothschild towards him. Rothschild, looking distrustful and somewhat scared but started to move forwards and then stopped about two yards away. "You must be kindly. You are not to beat me!" he said, squatting down. "Moysey Ilyich has sent me to you again. Don't be afraid, he says, go again to Yakov and tell him, he says, that there is no way of getting by without him. The wedding is on Wednesday... Yes. Mr Shapovalov is marrying his daughter to a finest hentleman... It will be a rich wedding, ooh-hoo!" the Jew added and screwed tight one eye. "I can't," said Yakov, breathing heavily. "I'm not well, my friend." He started again to play and tears spurted out of his eyes and fell on the violin. Rothschild listened attentively standing sideways on and his hands folded on his chest. The terrified, perplexed look on his face gradually changed to one of pain and sorrow, his eyes rolled, as if were experiencing a tormenting delight, and he exclaimed "Aaaah!" The tears slowly rolled down his cheeks and started to fall on his green jacket. Afterwards Yakov lay all day in bed and pined away. When in the evening the priest gave him confession and asked him if he remembered any particular sin he needed to confess, then, straining his weakening memory, Yakov remembered again the unhappy face of Martha and the terrified shriek of the Jew when the dog bit him, and he said in a scarcely audible voice "Give the violin to Rothschild." "It shall be done," said the priest. And now, in the town, everyone asks "Where did Rothschild get that wonderful violin?" Did he buy it, or steal it, or was it part of a debt?" He gave up the flute long ago and now only plays the violin. The same mournful notes pour out from his bow as used to come from his flute, but when he tries to repeat what Yakov played sitting in his doorway, then something so utterly mournful and piteous comes out that the audience cry, and he himself towards the end rolls his eyes and exclaims "Aaaah!" This new tune was so popular in the town that the merchants and officials continuously invited Rothschild to their places and made him play it a dozen times. Russian Herald. 1894 No 37. |

|

| Home | Lermontov | Other Pushkin | Onegin Book I | Book II | Book III | Book IV | Book V | BookVI | BookVII | BookVIII | Gypsies | Chekhov |